Sexual sanism permeates the ways our culture talks about and treats the “mentally ill,” “queer” people, and, more broadly, anyone who relates or reacts “inappropriately” to the world and people around them. As a discourse of oppression, it links the oppressions of queer and Mad people together, in a way that requires us to work towards our mutual liberation.

What do I mean by this? “Sexual sanism” is a label I’ve used to describe the ways in which sexuality and sanism are co-constructed in our society. In essence, an underlying assumption of the “insane” or the mentally ill is that they are, in some way, shape, or form, also sexually deviant, and this sexual deviance is a signal to their troubled minds; in turn, the sexually deviant are deemed to be “mentally ill,” with all their behavioral issues being an expression of a sexual identity thrown askew in their development. How can you tell if someone is insane? They are sexually deviant (which can mean a number of things—maybe they wear the “wrong” clothes, sleep with the “wrong” people, or don’t sleep with any people, or sleep with too many people). How can you tell if someone is sexually deviant? They have some kind of underlying mental illness condition. The dominant norm of behavior, then, determines what “normal” sexuality and “normal” neurosis is, and uses deviations from one of these norms as evidence of deviance in the other.

I came to this understanding of sexuality, sanism, and behavioral norms while doing historical research for my Master’s thesis in Sociology at the University of Alberta. Historically, “sexual sanism” was used in many ways, but its main use, by psychiatrists and psychiatrically-aligned laypersons, was to demonize and delegitimize lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or otherwise “queer” people. (Technically, the definitions of a “mentally ill person” under Canadian legislation would have included anyone who related to other people “inappropriately” and reacted to other people “inappropriately,” two norms which are highly culturally-contextual but, nonetheless, made “queer” and “insane” people practically one and the same.)

The effects of this kind of logic—which was generated by psychiatric policy—meant that queer people often lost their rights despite Canada’s supposed “decriminalization” of homosexuality in the 1960s (though gender-expansive expression was still criminalized for decades after that).[1] Several stories from my archival research support this statement.

Testimonies from the Psych Wards

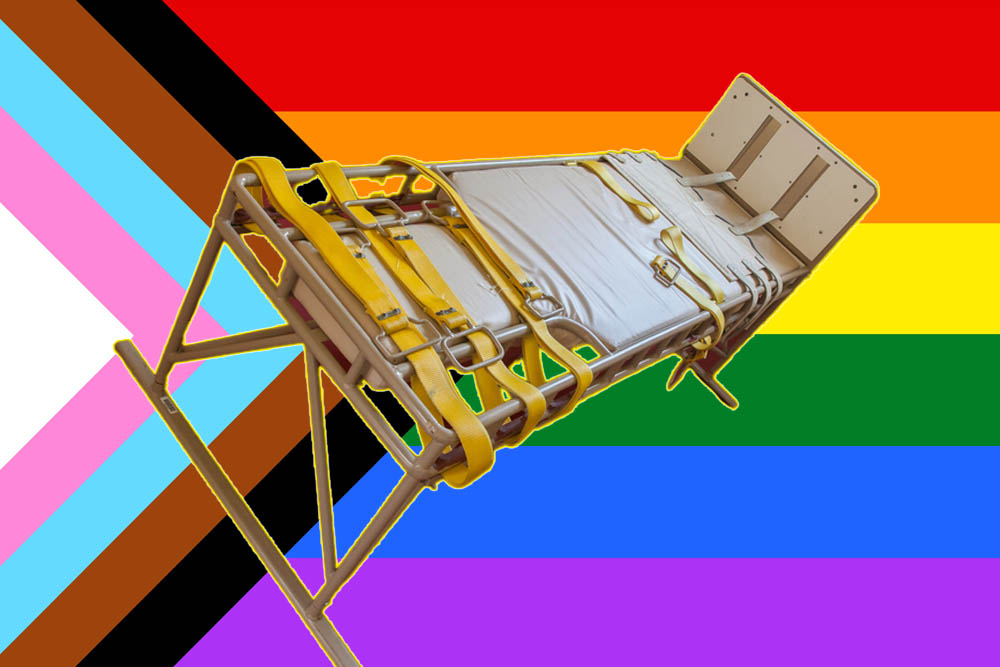

There were many “treatments” I found in these archives, including electroshock therapy and widespread aversion therapy in Canadian hospitals. Layperson publications included many stories and testimonies of queer peoples’ experiences in Canadian psychiatric institutions. Gemini, a newsletter for a Waterloo Gay Liberation movement (which can be found in Archives of Sexuality and Gender), asserted in 1971 that aversion therapy techniques—specifically, to condition homosexuals into heterosexuals—were widespread in Canadian psychiatric institutions, even after the general public began to condemn it.

Individual testimonies go into this in more detail. Susan White, a self-described “‘ex-crazy’ and currently unemployed therapist” in Winnipeg, wrote of her experiences in an article for The Body Politic, found in Archives of Sexuality and Gender. Her friends in the ward—both those she was treated alongside of, and those she helped to treat as a nurse years later—lost all memory of her after experiencing shock treatment. She described her own electro-convulsive therapy as feeling like “being hit with a sledgehammer.” White was also an outspoken lesbian. Her doctor, upon discovering that her questioning (but closeted) roommate was rooming with a lesbian, screamed “She’s rooming with a what?!!” and demanded the whole hall be reorganised to prevent such an arrangement. Simply talking to this woman was enough to cause conflicts with the nursing staff, with her deviant relating (lesbianism) becoming a problem for the entire ward staff to handle.

Sheila Gilhooly, an outspoken ex-mental patient activist in Vancouver in the 1970s-‘80s, frequently wrote of the ways in which ward staff attempted to “cure” her lesbianism, something she resisted through 19 shock treatments. She would only escape the psychiatric ward after pretending to be a “normal” woman. She did this by never presenting a “problem” for staff, not talking about her desire for women, and always acting cheerful, in essence, relating as a heterosexual, “sane” woman.

Even outside of the psych ward, psychiatry influenced the lives of queer/trans people in Canada to oppressive effects. Authors writing from clinical experience in the Gender Identity Clinic of the Clarke Institute, for instance, wrote that only a small minority tend to pass well as women, while “the more transvestitic males often appear very unfeminine, wearing obvious wigs and heavy pancake makeup in an attempt to cover their beard.” This kind of writing highlights the disgust and contempt psychiatrists held for their patients, even as they attempted to help them transition.

Notably, “The [Clarke Institute] tends to take a conservative view and requires a minimum period of cross-living of 1 year before commencing hormone therapy.” Patients were expected to navigate this trial-living themselves, and those who “require much support and demand assistance in. . . establishing their cross-gender role” are portrayed as emotionally immature and unstable. Any transgender woman who re/acted “inappropriately” in this way, or related inappropriately (by being improperly feminine, or by being attracted to women, or by not being attracted to men), was sorted into the category of “transvestite”—a clinical label which was used to delegitimize transgender women’s gender identities- while the transgender women who could relate and react “normally” (as defined by psychiatry, which included not having another clinical label like “schizophrenia” attached to them) would be deemed “proper transsexuals.”

One will notice that most of these stories are about women. Though I gathered no statistical information on the presence of women vs. men in psychiatric wards, what I will say is that, likely, sexism played a major role in queer and transgender women’s psychiatric oppression, which requires thorough feminist analysis. Though I was able to glean a few stories of queer men’s experiences in psychiatric wards, the majority of queer men who encountered psychiatric oppression were “sorted” into prisons and “psychiatrized” there, under “Dangerous Sexual Offender” legislation. The National Gay Rights Coalition, for instance, alleged that federal penitentiaries would refuse parole to gay prisoners who refused homosexual aversion therapy.

I outline these stories not only to discuss an historical process, however. What I hope to illustrate is that sexual sanism still permeates our discussions of queerness, Madness, or anything/anyone else who relates/reacts “inappropriately” to this day.

Back to the Present

Little has changed since the timeframe my study is based in.

In these earlier discourses, a deviant, hypersexual sexual instinct was used as “proof” of a transvestic identity which could, in turn, “prove” the trans person was inherently insane and criminal; in today’s day and age, sexualization continues to be used as a tool for delegitimizing trans women’s identities and ways-of-being. Politicians have called those who denounce the school censorship of trans-centred curriculum, as well as the outing of transgender kids to their parents, “groomers,” and their schools are grooming centres for “gender identity radicals.” Seemingly, this sexual sanist assumption has moved beyond separating trans people from each other to lumping ALL trans people into the “sexual predator” category. Julia Serano argues in her book Whipping Girl that this hypersexualization of transgender people—transwomen in particular—serves not only to delegitimize (which results in bans on hormone therapy, surgeries, or other forms of gender-affirming care), but also to demonize, to turn trans people into monsters and societal scapegoats.

This kind of discourse has clear precedent in Canadian history. Bill C-83, for instance, was labeled by gay liberation activists as “excessively punitive,” using the “gross indecency” charge to confine queer people to psychiatric treatment in prison indefinitely after one offence. When activists brought their critiques to court, Liberal legislators attacked them with the very same “grooming” language being used today. It was not until an academic stepped in and presented his research into DSO legislation and its failures that legislators even began to reconsider the bill. (Notably, he said many of the same things the activists had said, including that psychiatrists were more likely to label homosexuals as “psychologically damaged” than heterosexuals, and to use this label to support conviction decisions.)

More recently, bills have been introduced to restrict gender-affirming care for people with autism and other “mental health conditions,” mimicking the way in which schizophrenia was used to differentiate mentally ill people from “true” transsexuals. In Canada, the Million March for Children has risen in prominence to protest the inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) education in school curriculums, in the name of protecting “vulnerable children” from harmful language and “crazed” agendas. Danielle Smith, the premier of Alberta, along with the United Conservative Party, has introduced bills which would forcibly out trans children to their parents should they decide they want to use different pronouns at school—a procedure which is not at all medical, and yet, still poses a threat, because the UCP has decided trans people are “insane” and sexually deviant.

Conclusion: Our Response?

There is no easy way to respond to this moment. Right-wing movements and actors continue to see both Mad and queer people as monsters, less than human. While there is no easy solution, I would argue that we can start by knowing our history and being able to name it; to see where our oppressions overlap, where they diverge, and where they parallel; and how our communities can see and support each other through it all. Angela Davis once said that “You have to develop organizing strategies so that people identify with the particular issue as their issue” (emphasis added).

Psychiatric oppression must become a queer issue; 2SLGBTQIA+ oppression must become a Mad issue; and our mutual liberation must become a shared goal. We can do this by resisting the carceral arms of psychiatry, where we can; resisting involuntary “treatment” practices (which would be levied against queer people disproportionately, as a group who relates and reacts inappropriately to cis-heteronormative norms); and honoring diverse ways of living, being, and acting in the world. It also means planning to refuse to comply with the waves of oppressive policies we are seeing across both Canada and the United States. This includes at the university level. On-the-ground activists protested Bill C-83 in Canada, but it took Professor C. Greenland of McMaster University saying what they were saying (albeit, backed by years of research into DSO legislation) for legislators to listen.

We can see that sanism and anti-queer rhetoric continue to go hand-in-hand, and our best response to this moment should come with an understanding of our shared queer/Mad history and a solidarity across lines of oppression.

[1] Gary Kinsman, a leading scholar of sexual regulation by the Canadian government, goes into more detail on how the “decriminalization” of homosexuality led to a host of “dangerous sexual offender” or “perversity” laws as a way to continue the oppression of non-heterosexual people in his book The Regulation of Desire: Queer Histories, Queer Struggles.

***

Mad in America hosts blogs by a diverse group of writers. These posts are designed to serve as a public forum for a discussion—broadly speaking—of psychiatry and its treatments. The opinions expressed are the writers’ own.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1445381849-d8f276a75cbd42c38cc3ed367dfdd69f.jpg?w=120&resize=120,86&ssl=1)